4.1 Introduction4.2 Basic Elements of CMN4.2.1 The Role of the Measure Element4.2.2 Defining Score Parameters for CMN4.2.3 Special cases in staff definitions4.2.4 Re-definition of Score Parameters4.2.5 Notes, Chords and Rests in CMN4.2.6 Timestamps and Durations4.3 Advanced CMN Features4.3.1 Beams4.3.2 Ties, Slurs and Phrase Marks4.3.3 Dynamics in CMN4.3.4 Tuplets4.3.5 Articulation and Performance Instructions in CMN4.3.6 Instrument-specific Symbols in CMN4.3.7 Ossia4.3.8 Cue4.3.9 Directives and Rehearsal marks4.3.10 Repetition in CMN4.4 Common Music Notation Ornaments4.4.1 Encoding Common To All Ornaments4.4.2 Mordents4.4.3 Trills4.4.4 Turns4.4.5 Other Ornaments4.4.6 Ornaments in Combinations

4Repertoire: Common Music Notation

The module described in this chapter offers the means to describe music in so-called ‘Common Music Notation’ (CMN, sometimes referred to as ‘Common Western Music Notation’). For this purpose, it provides a number of special elements and adds several attribute classes to elements from the 2 Shared Concepts in MEI module.

4.1Introduction

This chapter is supposed to frame the repertoire target by the module, i.e., what is Common Music Notation?

4.2Basic Elements of CMN

This section describes the use of basic features of MEI important for encoding CMN material. Most of the elements discussed here are defined in chapter 2 Shared Concepts in MEI of these Guidelines, but are used in music from the CMN repertoire in specialized ways.

4.2.1The Role of the Measure Element

Arguably, the most important element of the CMN module is the <measure> element. It is used as a structural unit inside <section> elements and acts as a container for ‘events’ from the model.eventLike class, such as notes, chords and rests as well as ‘control events’ from the model.controlEventLike class, such as slurs and indications of dynamics.

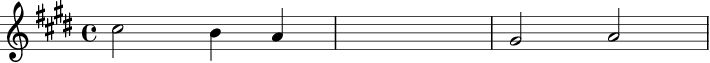

The following example demonstrates the use of the <measure> element:

A <measure> slices the flow of a score or part into chunks that normally comply with a duration determined by the meter defined within a preceding <scoreDef> or <staffDef> element. Each staff in the source material is represented by a <staff> element. As the order of the staff elements in the file does not have to reflect their order in the original document, to eliminate confusion they should always refer to a <staffDef> element, using either an @n or @def attribute. Whereas the @def attribute uses the xs:anyURI datatype, the @n value refers to the closest preceding <staffDef> or <layerDef> with the same value in its @n attribute.

Each <staff> may hold a number of <layer> elements to reflect multiple ‘voices’. Just as with <staff>, the order of the <layer> elements in the file does not have to reflect their original order in the document, so they also possess @n and @def attributes for association with the appropriate layer definition.

Later in the file:

4.2.2Defining Score Parameters for CMN

When encoding a score in CMN, MEI relies on the following elements from the 2 Shared Concepts in MEI module:

A <scoreDef> element is used to specify the common parameters of a score, e.g., key and meter. The most important attributes for this purpose are:

The following example describes a score in common time with 3 flats:

For encoding more complex time signatures, simple mathematical symbols such as asterisks and plus signs are allowed in @meter.count.

Non-standard key signatures have to be encoded with a <keySig> element.

Other attributes allow the description of default page and system margins and fonts for text and music:

There are other attributes that allow the specification of many further details of a score. These are available from the element definitions accessible at <scoreDef>, <staffDef>, <staffGrp> and <layerDef>.

When content is provided for <scoreDef>, it must contain a <staffGrp> element. This element is used to gather individual staves and other staff groups. This is useful for collecting instrumental or vocal groups in a large score, such as woodwinds, brasses, etc., and for assigning a shared label to the group, using the <label> and <labelAbbr> subelements. The <staffGrp> element is also used for the two staves of a grand staff. The @bar.thru attribute on <staffGrp> allows one to specify whether bar lines are drawn across the space between staves of that group or only on the staves themselves.

A <staffDef> element is used to describe an individual staff of a <score> or performer <part>. It bears most of the attributes described above. The <label> and <labelAbbr> subelements may be used for providing staff labels for the first and subsequent systems.

Every <staffDef> must have an @n attribute with an integer as its value. The first occurrence of a <staffDef> with a given number must also indicate the number of staff lines via the @lines attribute.

The order of <staffDef> elements within <scoreDef> follows the order of staves in the source document or planned rendering. The individual <staff> elements within a <measure> refer to these <staffDef> declarations using their own @n attribute values. Therefore, the encoding order of staves within a measure does not have to mimic the order of the <staffDef> elements with <scoreDef>.

In addition to the parameters inherited from <scoreDef>, the following attributes are important for <staffDef> elements:

A staff with a tenor clef is encoded as in the following example:

In the case of transposing instruments, the key-related attributes described above may be used to override the written key expressed in the <scoreDef> element. As a basic principle, MEI always captures written pitches, so the @trans.diat and @trans.semi attributes may be used to indicate the number of diatonic steps and semitones to calculate sounded pitch from written pitch. The piccolo and E♭ clarinet staves in the example below utilize these attributes:

There are a number of additional elements that can be used as children of <staffDef> in order to describe additional features of the staff, such as the color of a clef or a key signature added in a different hand. These elements include:

With the exception of <label>, these elements may also occur within the flow of musical events captured in a <layer>, since they are members of model.eventLike. In the layer context they function as milestones and affect all following content assigned to the layer (even in subsequent measures) until their information is again overridden either by the same element bearing different information or a <staffDef> or <scoreDef>. In this context, it is also possible to combine them with the elements described in chapters 11.1 Critical Apparatus and 11.2 Editorial Markup of these Guidelines.

Such flexibility as this may require close inspection of an encoding to retrieve the correct definitions for a given staff. As a general rule, the closest preceding and most specific element provides this information: For example, a <keySig> in the preceding measure is more relevant than a <staffDef> at the beginning of the section, which is more relevant than a <scoreDef> at the beginning of the score. However, a section-specific <scoreDef> that provides only information about the meter does not override the more specific information about key signature gathered from a <staffDef> for a transposing instrument.

Every <staffDef> may contain a number of <layerDef> elements, which may be used to establish default values for the distinct layers sharing one staff. MEI does not use the term ‘voice’ to describe these ‘musical threads’ because that term implies continuity across measure boundaries. Given the sometimes arbitrary relationships between these threads from measure to measure as well as across staves, MEI uses the more neutral term ‘layer’.

4.2.3Special cases in staff definitions

Usually <clef>, <key>, and <meterSig> apply to a whole staff.

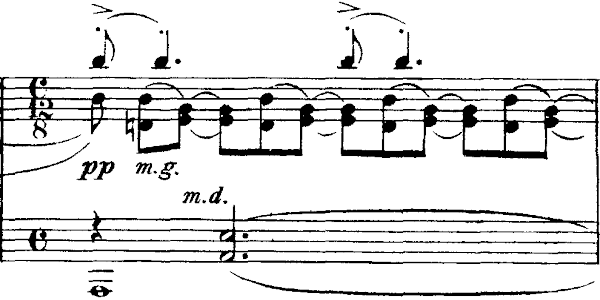

In some rare cases one can find different meters in different layers, as seen in Maurice Ravel’s Oiseaux tristes.

In these cases it is necessary to encode each <meterSig> for the staff as child of the corresponding <layerDef>:

When multiple time signatures appear next to each other the <meterSigGrp> element has to be used.

4.2.4Re-definition of Score Parameters

Sometimes it is necessary to re-define the parameters of a score or a staff. For example, a score may change keys, the number of staves, or use different layout settings. Likewise, a staff may change its clef, change the number of layers, or become invisible. To accommodate these changes, <staffDef> is allowed to occur in the following locations:

- within the description of staff groups; that is, in <staffGrp>,

- within the content of a <measure>,

- between measures; that is, directly within <section> and <ending> elements, and

- between sections and endings; that is, directly within a <score> or <part> element.

In addition, <scoreDef> is allowed to occur:

- within sections and endings; that is, inside <section> and <ending> elements; and

- between sections and endings; that is, directly within a <score> or <part>.

It is also possible to include <scoreDef> and <staffDef> in staves and layers when the MEI All schema is in use; however, this practice is not recommended for the CMN repertoire.

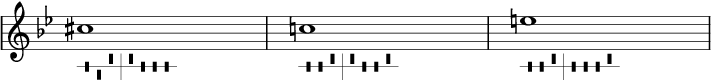

The following example shows how to change the key and meter signatures within a score. The @keysig.cancelaccid attribute may be used to control the position of the cancellation accidentals of the key signature change, while the @keysig.visible can be used to hide the key signature entirely.

4.2.5Notes, Chords and Rests in CMN

4.2.5.1Notes

Undoubtedly, the most important element for any music notation representation is the <note> element, which is defined in section 2.2.3 Basic Music Events. This section describes the usage of <note> in the CMN repertoire as well as CMN-specific additions to the basic definition in the shared module.

4.2.5.1.1Basic Usage of Notes in CMN

In CMN, notes are determined by three basic parameters:

- pitch name (using @pname)

- octave (using @oct)

- duration (using @dur)

A single note, in this case a quarter note C4, is therefore encoded as:

The default values for @pname and @oct conform to the Scientific Pitch Notation (SPN) (also known as American Standard Pitch Notation); that is, the letters A–G indicate the musical note name of a pitch, and the numbers 0–9 indicate the octave range to which a note belongs. @pname values differ from this convention only by using lower case values for pitches (a–g instead of A-G). The value for @oct changes between B and C, that is, octave ranges go from C, D, …, G, A, to B. For example, middle C or c' (the C in the middle, i.e., fourth C key from left, on a standard 88-key piano keyboard) is represented on the first ledger line in G clef notation and labelled as C4, in the naming convention of SPN. The note one semitone below would be labelled B3, and A4 would refer to the first A above C4.

The usual CMN-specific values for @dur are:

1: whole note

2: half note

4: quarter note

8: eighth note

16: sixteenth note

…:

2048: 2048th note

Additionally, the following two values borrowed from mensural notation are allowed, as they sometimes also appear in CMN:

breve: double whole

long: quadruple whole

Please note that their mensural counterparts bear different names in order to clearly distinguish between repertoires.

Dotted durational values are accommodated by the @dots attribute, which records the number of written augmentation dots. Thus, a dotted quarter note is represented as in the following example:

4.2.5.1.2Grace Notes

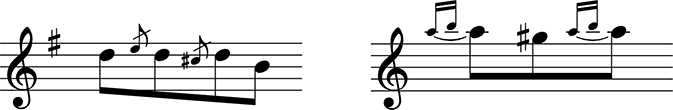

The CMN module adds two optional attributes, @grace and @grace.time, to <note> and <chord>. The presence of the @grace attribute indicates a grace note or chord.

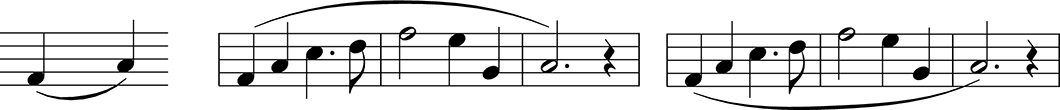

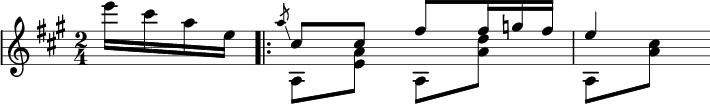

The encoding of the left-most example would look like this:

Grace notes are not counted when determining the measure’s conformance to the current time signature. Therefore, the @dur attribute records only the written rhythmic value of the grace note. The time necessary for the performance of grace notes can be unspecified, calculated based on taking time from other non-grace notes, or specified precisely using the @dur.ges attribute.

The values of @grace indicate from which note time is ‘borrowed’ to perform the grace note: The preceding note, in which case the value unacc (unaccented) is used, or the following note, when the value acc (accented) is appropriate. Technically, this value determines if the note following the grace will keep its original onset time or will be slightly delayed to allow the grace note itself to be accented. Sometimes it is not clear how to perform a grace; in these situations the value unknown allows one to indicate a grace note while unambiguously stating that its performed duration remains unknown.

The @grace.time attribute is only to be used in combination with the @grace attribute. It records the amount of time (as a percentage of the written duration) that the grace note should ‘steal’ from the preceding note (when @grace="unacc") or the following note (when @grace="acc").

Grace notes can be placed within a <graceGrp> element, which itself allows all values for @grace as explained above. The optional @attach attribute is used to record whether the grace note group is attached to the following event or to the preceding one. The <graceGrp> element can be used with single or multiple grace notes.

More information about grace notes in the context of other CMN ornaments is available in chapter 4.4 Common Music Notation Ornaments.

4.2.5.2Chords

Often we find multiple notes that are not sounding in succession but sounding simultaneously. These chords in MEI are basically defined as a container of notes that are stemmed together.

4.2.5.2.1Chords in CMN

A chord is any set of pitches consisting of multiple notes that are to be played simultaneously and are usually grouped together visually with a single stem. In MEI the <chord> element functions as a container for all participating notes. Also it features many attributes that are allowed for notes, e.g., usually all notes in a chord have a common duration, so it can be applied to the whole chord within it’s @dur attribute.

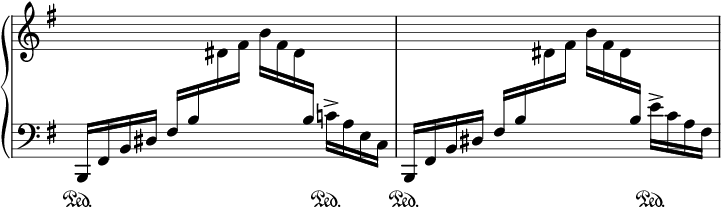

Some notational features like articulations or lyrics are connected to a whole chord instead of a single note. Therefore elements like <artic> or <verse> are also allowed as children of <chord> elements. In the following example from Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in C-sharp minor, Op. 3, No. 2 all chords carry an accent.

4.2.5.2.2Stem Modifications

The @stem.mod attribute accommodates various stem modifiers found in the CMN repertoire. These symbols are placed on a note or chord’s stem and generally indicate different types of tremolo and Sprechstimme. The following values are allowed:

1slash: 1 slash through stem

2slash: 2 slashes through stem

3slash: 3 slashes through stem

4slash: 4 slashes through stem

5slash: 5 slashes through stem

6slash: 6 slashes through stem

sprech: X placed on stem

z: Z placed on stem

The @stem.mod attibute is normally used in accordance with practices described in section 4.3.5.3 Tremolandi.

The CMN module makes the att.stems.cmn attribute class available, which adds the optional @stem.with attribute to <note> and <chord>. The attribute @stem.with allows for the indication of a stem that joins notes on adjacent staves.

The following code demonstrates one method of encoding the first chord in the last measure in the image above. The @stem.with attribute must occur on all the notes or chords attached to the cross-staff stem.

Alternatively, the encoder may choose to treat the notes in the lower staff as logically belonging to the top staff and to ‘displace’ them using the @staff attribute on <note>. Some use cases, however, may require filling the time that those notes would normally occupy using the <space> element described in section 2.2.4.5 Event Spacing. Using this mechanism, the example above could also be encoded like so:

The choice between these two methods of representing material that crosses staves is often software-dependent.

Whereas @stem.with can be used to define stems that connect notes across different staves (cross-staff chords) @stem.sameas is meant for describing a stem that connects two notes pertaining to different layers within the same staff.

The typical scenario for @stem.sameas is orchestral scores where two wind instruments are notated on one single staff. Normally, the notes have individual stems pointing in opposite directions. However, it is common engraving practice that notes of the same duration are often stemmed together between the parts encoded in separate layers. The following example demonstrates this practice in the wind instruments (bassoons and trumpets in meas. 1 - 3, horns in meas. 3)

The following code represents an encoding of shared stems in the bassoon and trumpet staff using @stem.sameas.

4.2.5.3Rests

The @dur attribute on <rest> captures the written duration of the rest and allows the same values as on <note> and <chord>. The CMN module also makes three more elements available for special forms of rest:

4.2.5.3.1Measure Rests

The <mRest> (measure rest) element is used to indicate a complete measure rest, independent from the meter of the current

The @cutout attribute provides for the description of the rendition of the <mRest>. If @cutout is set to ‘cutout’ (the only value allowed), then the complete staff including the staff lines will not be rendered for this measure.

It is a semantic error to mix an <mRest> with other events in the same <layer>. However, other ‘control events’, such as <fermata>, may be used at the same time as <mRest>.

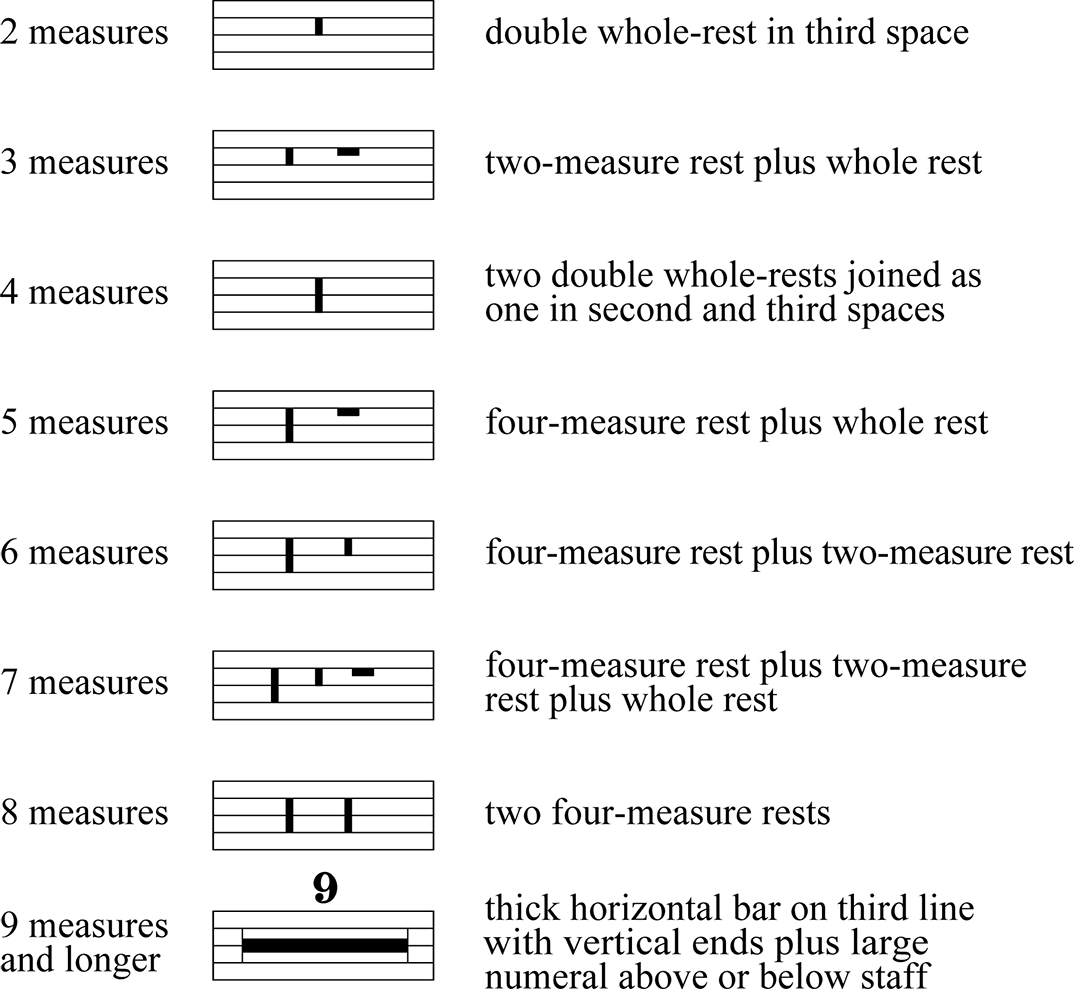

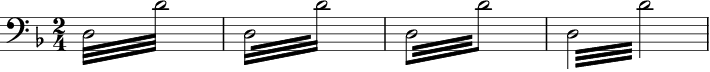

4.2.5.3.2Multiple-Measure Rests

The <multiRest> (multiple measure rest) element is used to encode multiple measures of rest. It is commonly used in performer parts, but due to the problem of synchronicity with other staves, it is never found in scores. A numeric value, stored in the @num attribute, indicates the number of resting measures. The older visual forms displayed below (often called Kirchenpausen) are not captured by <multiRest>, but may be created by rendering software. You may force modern block rests by using the @block attribute.

4.2.5.3.3Empty Measures

The <mSpace> (measure space) element is closely related to the <space> and <mRest> elements. It is used to explicitly indicate that a layer has no content but that no information is missing from the encoding.

4.2.6Timestamps and Durations

MEI offers multiple ways of defining onsets and offsets of timed musical events such as notes and slurs. The most common and most musician-friendly approach to this is through the use of a combination of the attributes @tstamp and @dur, which are made available by the attribute classes att.timestamp.log (inherited by att.controlEvent) and att.timestamp2.log, both from the shared module.

The timestamp (@tstamp) of a musical event is calculated in relation to the meter of the current measure and resembles the so-called ‘beat’ position. In a common time measure with four quarter notes, the timestamp of each quarter equals its beat position in the measure: The first quarter has a timestamp of 1, the second has a timestamp of 2, and so on. MEI defines the value of @tstamp as a real number; the second eighth note position in a measure would thus be represented by the value of "1.5". The range of possible values is defined as starting with zero and ending with the number of metrical units in a measure (the ‘numerator’ in a time signature) + 1. This allows the capture of all graphical positions starting from the left bar line ('0') and ending with the right bar line of the measure ('5', in the case of 4/4 time).

For expressing durations, MEI offers the @dur attribute. This attribute is described in section 4.2.5.1.1 Basic Usage of Notes in CMN.

For ‘spanning’ elements like slurs, which are members of the model.controlEventLike class, it is often more intuitive to record two timestamps – one for the onset of the event and one for its termination. Because the termination of the event may be in a succeeding measure, the second timestamp (@tstamp2) has a slightly different datatype than the one marking the initiation of the event. Its datatype is constrained to values following the formula "xm + y", where x is the number of full measures that this particular feature lasts (or the number of bar lines crossed) and y is the timestamp in the target measure where the feature ends. The timestamp is expressed using the same logic as described above. For example, a value of "0m+3" in 4/4 time indicates that the element bearing this attribute, a slur for example, ends on beat 3 of the same measure where it started. A value of "1m+1.5" would indicate an end on the second eighth note of the following measure. In 6/8 time, the value "2m+3" means that the feature ends two measures later on the third eighth note.

4.3Advanced CMN Features

Over time, in addition to the basic features of note, chord, and rest, many other symbols have been added to CMN. The following section describes some of these symbols and introduces their handling in MEI.

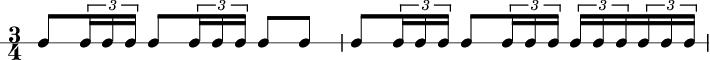

4.3.1Beams

A very common feature of music from the CMN repertoire is the beaming of eighth or shorter notes. MEI provides two elements for the explicit encoding of features joined by beams.

Use of the <beam> element is straightforward. The beamed notes, rests, or chords are simply enclosed by the <beam> element:

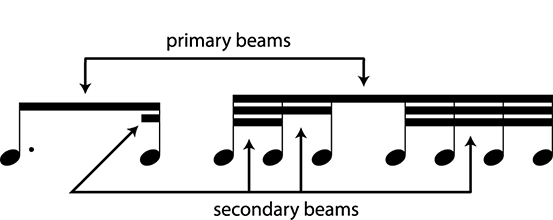

Whereas in music notation every note value shorter than an eighth adds another beam (sometimes referred to as ‘secondary beams’), in MEI only one beam element is used, no matter the durations of the contained notes. The visual rendition of a set of beamed notes is presumed to be handled by rendering processes.

From the 19th century onwards, it became quite common to break secondary beams to increase readability of longer beamed passages. The optional @breaksec attribute on <note>s and <chord>s under the beam may be used to encode the breaking of secondary beams after the note or chord bearing the attribute. The value of @breaksec indicates the number of continuous beams. For example:

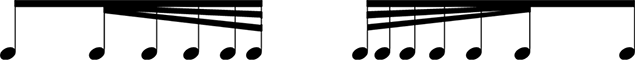

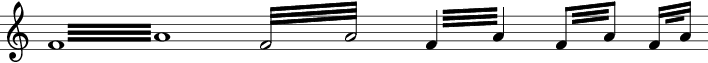

In the music of the second half of the 20th century, it is quite common to indicate acceleration or deceleration using converging (feathered) beams as in the image below:

The encoding of such a beam is accomplished using the @form attribute of the beam, which allows the following values:

acc: Beams gradually diverge.

rit: Beams gradually converge (into one).

mixed: Beams diverge and converge arbitrarily.

norm: The beam is rendered as usual (default).

The duration of notes, rests, or chords under a beam which carries the @form attribute with a value of ‘acc’, ‘rit’, or ‘mixed’ must be treated specially. The first and last contained elements must specify a duration which matches the number of beams displayed at the point of these events. In the case of a ‘mixed’ beam, each event at the point of change in the number of secondary beams must carry a @dur attribute. Beams like this may be encoded thusly:

Beams that connect events on different staves may be encoded in two different ways. First, a single-layer approach may be taken that treats the events lying under the beam as logically belonging to the same layer as the initial event but visually ‘displaced’ to an adjacent staff. In the example above from Moritz Moszkowski’s 12 Pianoforte Studies for the left hand, Op. 92, MoszWV 117 this method makes even from a semantic perspective perfect sense. It can be achieved with an additional @staff attribute value that contradicts the ‘normal’ staff placement indicated by the @n attribute of their ancestor <staff>.

In other contexts however, a staff-by-staff methodology may be employed in which the notes are encoded according to the staff on which they appear. This encoding style requires that each <beam> element account for the total time encompassed by the beam; that is, each <beam> must use one or more <space> elements to account for the time occupied by notes on the opposing staff. For example, the time used by the first two notes of the beam must be represented on staff number 1 and the time taken by the last two notes of the beam must be filled on staff number 2.

Downstream processing needs are the determining factor in the choice between the two alternative encoding methods.

Due to the potential problem of overlapping hierarchies, the <beam> element only allows the encoding of beams that do not cross bar lines. When beams cross bar lines, the use of the <beamSpan> element is required. Unlike <beam>, the <beamSpan> element does not contain the beamed notes as its children. Instead, it references the @xml:id values of all affected notes in its @plist attribute and denotes the initial and terminal notes of the beam using @startid and @endid attributes. This configuration allows beams to cross measure boundaries. The following example from Erwin Schulhoff’s Violin Sonata demonstrates a typical example of such hierarchy-crossing beams:

In addition to the explicit encoding of beams accommodated by the <beam> and <beamSpan> elements and the @beam attribute, MEI allows for specification of default beaming behavior using the following attributes on <scoreDef>, <staffDef>, and <layerDef>:

beam.group: Provides an example of how automated beaming (including secondary beams) is to be performed.

beam.rests: Indicates whether automatically-drawn beams should include rests shorter than a quarter note duration.

The @beam.group attribute can be used to set a default beaming pattern to be used when no beaming is indicated at the layer level. It must contain a comma-separated list of time values that add up to a measure in the current meter, e.g., 4,4,4,4 in 4/4 time indicates that each quarter note worth of shorter notes should be beamed together. Parentheses can be used to indicate sub-groupings of secondary beams. For example, (4.,4.,4.) in 9/8 meter indicates one primary beam per measure with secondary beams broken at each dotted quarter duration, while (4,4),(4,4) in 4/4 will result in a measure of 16th notes being rendered with a primary beam covering all the notes and secondary beams for each group of four 16th notes.

The @beam.group attribute is available on <scoreDef>, <staffDef>, and <layerDef> elements, making it possible to set different beaming patterns for each of these. Also, the beaming pattern can be changed anywhere score parameters may be changed, for example, at the start of sections. This beaming "directive" can be overridden by using <beam>, <beamSpan>, or @beam attributes as described above. If none of these beaming specifications is used, then no beaming is implied. Default beaming can be explicitly ‘turned off’ by setting @beam.group to an empty string.

4.3.2Ties, Slurs and Phrase Marks

One of the most specific features of CMN is the use of ‘curved lines’ which connect notes. These lines are used to indicate various musical features, depending on their context.

A tie is a curved line connecting two notes of the same pitch. The purpose of a tie is to join the durations of both notes, so that the first note sounds for the combined duration. In other words, there is only one onset for both notes.

In MEI, ties can be encoded in different ways, depending on the level of detail that

the encoder wants to preserve. The simplest solution is to use the @tie attribute found on <note> and <chord>.

This attribute allows three values:

i (initial): Marks the start of a tie

m (medial): Marks a participant in a tie other than the first or last

t (terminal): Marks the end of a tie

The scope of the @tie attribute is the musical <layer>; that is, a tie started in one layer may only be ended by a subsequent musical event with a @tie attribute with an m or t value in the same layer. The tie-terminating event may lie in the following measure.

When @tie is used on chords, it functions as a shorthand indication for multiple tie markings; that is, a separate tie is drawn for every pitch in the chord that remains unchanged in the succeeding chord.

This is equivalent to the following, more verbose version:

A slur is a curved line that connects a group of notes of different pitch. It normally indicates that an instrument-specific performance technique should be applied to the affected notes. For example, in notation for winds, the notes should be played in one breath, while a single bow is indicated for string instruments.

In MEI, slurs may be encoded in a similar way to ties: <note> and <chord> bear a @slur attribute that allows the commencement or ending of a slur at this element. The allowed values, however, are slightly different: The i, m or t are followed by a single digit in the range 1 to 6, as in the following example:

The reason for this difference is that slurs, unlike ties, may overlap, so that a second slur may start while the first slur is still ongoing. The digit indicates the level of nesting of slurs on the note; ‘1’ indicates no nesting, while ‘2’ indicates the existence of 2 slurs in which this note participates, and so on. In the example below, the second and third quarter notes lie under 2 slurs. The second note is covered by the slur that begins on the preceding note and by the one that it starts. The third note is affected by the slur that begins on note one and by the one that starts on note two.

To support analytical operations, @slur may take on more than one value. For example, the example above may be more explicitly encoded as:

In this encoding, the notes in the beamed group are marked as participating in two slurs – one connecting just the beamed notes and one connecting the first and last notes of the layer. In ‘nested’ slurs like this, the function of the slurs is usually different. Here, the slur connecting the 8th notes indicates legato performance, while the longer slur functions as a phrase mark.

While ties are not normally allowed to cross layers or staves, slurs may. The following example demonstrates how cross-staff slurs may be encoded using the @slur attribute:

Slurs and ties that cross system or page breaks are often split into two separate symbols for rendering. One slur or tie ends at the last bar line, another one starts at the beginning of the new system. MEI expects this to be the default rendering behavior, so that in situations like these, the regular @tie or @slur attributes are sufficient to describe both curved lines resulting from the split.

Sometimes, however, one of these two symbols is missing in the document, or the encoder wants to provide additional (often visual) information about the slur or tie. In these cases, using an attribute is not an adequate solution. Therefore, MEI offers dedicated <tie> and <slur> elements. A third element, <phrase>, is used to identify a unified melodic idea (in German: Phrasierungsbogen), whereas the <slur> element is used as a generic element for all curved lines (in German: Bogensetzung) except ties. All three elements have nearly identical models.

Another reason for using elements instead of attributes for ties, slurs, and phrase marks is that only elements may be combined with the functionality provided in chapters 11.2 Editorial Markup and 11.1 Critical Apparatus of these Guidelines.

Although these elements are allowed within a <layer> to accommodate unmeasured notation, by convention in CMN they are normally placed inside <measure>, after the encoding of staves, alongside other so-called ‘control events’.

Obviously, to be complete the slur in the above example needs to be ‘attached’ to the notes somehow. The ‘vertical assignment’ can be indicated for the example above using the @staff and @layer attributes like so:

For the ‘horizontal assignment’, the encoder may choose between two different mechanisms. The first uses two timestamp attributes as described in section 4.2.6 Timestamps and Durations. The start and end points of the slur may be indicated thusly:

By using @tstamp and @tstamp2 attributes, the encoder denotes a rather loose connection – the slur (or tie) is attached to a certain position in the measure, not to a specific note or chord. If the encoder wants to specify a close connection to a particular event, the @startid and @endid attributes may be used instead. Here, the @xml:ids of the first and last note of the slur are referenced. This mechanism also allows the crossing of layers and staves.

For human readability, it is recommended to encode <slur>, <tie> and <phrase> features in the <measure> where they begin; that is, in the measure that holds the element referenced by @startid. On the other hand, for machine processability, it may be desirable to place <slur>, <tie>, and <phrase> elements in the measure where they end or even in the last measure regardless of their beginning and ending points in the music. This last option makes all references contained within these elements ‘back references’. Back references are necessary when using processing software that treats the encoded file as a stream; that is, programs that process the file without creating an in-memory representation of its contents.

When using the <tie>, <slur> or <phrase> elements, the curvature of the line may be described using the @curvedir, @bulge and @bezier attributes. Whereas the first attribute allows only specification of the slur’s vertical placement, the others give increasingly more precise control of the curve.

If the encoder wishes to draw attention to the appearance of a slur or tie in a given source, the @facs attribute may be used instead of (or in addition to) the curve description attributes to point to a graphic image or a zone within an image (see 12.1 Facsimiles).

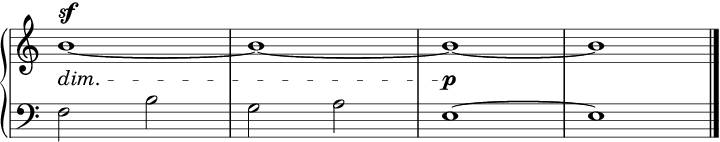

4.3.3Dynamics in CMN

Common Music Notation provides two different methodologies for expressing the volume

of a note, phrase, section, etc. The first is a verbal instruction providing such

information in human language, possibly in an abbreviated form. An example is the

word piano, indicating a quiet volume, often abbreviated as p. In MEI, verbal instructions like this are encoded using the <dynam> element from the Shared module (see chapter 2 Shared Concepts in MEI):

By convention, <dynam> elements, like <slur> and other elements belonging to the model.controlEventLike class, are encoded at the end of the <measure> to which they belong. This requires <dynam> to be assigned to a certain <staff> using the @staff attribute, whose value refers to the target element’s @n attribute. In the absence of other information, all layers within the staff are assumed to have the same dynamic marking.

However, when the layers of a staff have different dynamic indications, the @layer attribute may be used to associate a dynamic marking with a particular layer:

A suitable MIDI value may be assigned to a dynamic marking using the @val attribute:

The location of a dynamic marking in relation to a staff may be specified using the @place attribute, which may be given as above, below or within the staff or even between two staves:

Dynamics must also be associated with a particular time point in a measure, using the @tstamp, or with a particular event, using the @startid attribute. Linking a control event with measures and events is discussed in section 4.2.6 Timestamps and Durations:

Dynamics which do not have an explicit endpoint are often referred to as ‘instantaneous’. On the other hand, some dynamic directions indicate a continuous change that must have a defined end point. It is possible to specify the logical scope of continuous dynamic marks using the attributes @tstamp2, @dur, @dur.ges, or @endid. Additionally a corresponding ending value for MIDI output may be given in the @val2 attribute.

To capture the fact that the crescendo in the example above continue until the first beat of the next measure, they may be marked:

Any combination of @tstamp, @startid, @tstamp2, and @endid attributes may be used to define the scope of a dynamic, although the @tstamp and @tstamp2 or the @startid and @endid combinations are the most logical combinations. For example, the following alternatives are all possibilities for encoding up a crescendo. The choice of attributes is often task or processor dependent.

All musical elements affected by the <dynam> may be explicitly specified using the @plist attribute, which contains @xml:id attribute value references:

It is recommended that the list of references in @plist include all participants in the dynamic marking, including the first and last notes as in the preceding example, even though they are duplicated by @startid and @endid attributes.

In addition to verbal instructions, Common Music Notation uses graphical symbols to indicate ‘continuous’ dynamics. These crescendo and decrescendo (or diminuendo) symbols are encoded in MEI using the <hairpin> element. It also is a member of the model.controlEventLike class, which means it too is used just before the close of a <measure> element, following the encoding of all staves. The required attribute @form specifies the direction of the symbol by taking one of two possible values: cres (growing louder) or dim (getting softer).

Marking the logical extent of hairpins is possible using the same attributes as for <dynam>.

The following example from Béla Bartók’s Mikrokosmos, Sz.107 shows a diminuendo between two staves that begins on the first beat (in the current measure) and ends on the first one in the penultimate measure. The duration is highlighted with a dashed line, which can be indicated with the @extender attribute.

4.3.4Tuplets

Tuplets indicate a localized change of meter; that is, a given duration in the regular meter is divided between a group of notes with irregular (according to the current meter) rhythmic values. The most common tuplet is a so-called ‘triplet’, in which three notes take the time normally occupied by two.

The relation of the tuplet to the underlying meter is specified using the @num and @numbase attributes, where @num specifies the number of replacing notes and @numbase specifies the number of notes of the same duration to be replaced. For example, when three eighth notes replace one quarter note in common time, @num takes a value of "3", whereas @numbase reads "2", because a quarter note in common time is normally divided into two eighths. When three quarters replace two in the same meter, @numbase also reads "2". The combination of these attributes may be read as "3 in the time of 2" in either case.

The duration of the entire tuplet may be encoded using the usual ‘power of 2’ values, e.g., 1, 2, 4, etc., in the @dur attribute if necessary.

Tuplets are often highlighted using brackets above or below the affected notes. The presence and position of these brackets can be encoded using the @bracket.place (above / below) and @bracket.visible (true / false) attributes.

Usually, however, tuplets are rendered with a bracket (@bracket.visible="true") and a single number (@num.format="count" and @num.visible="true"), as seen in the example above. However, the number-to-numbase ratio may be provided in addition to, or in some cases as a replacement for, the bracket. The @num.format attribute indicates whether a plain number (the value of @num) or a ratio (comprised of @num and @numbase, e.g., "3:2") should be displayed and @num.visible indicates the general presence of such a number.

Further visual control comes with the @num.place and @bracket.place attributes, that allow specific placement of the number and the bracket above or below the staff.

In addition to <note> elements, <tuplet> may contain other elements, such as <rest> or <space>, to match the content of a source document or an intended rendering. In particular, the <beam> element is allowed so that custom beaming may be indicated, e.g., a septuplet may be divided into a group of three plus a group of four notes.

The <tuplet> element may also be used for repetition of the same pitch; that is, a single note or chord may be the only content of the tuplet. In some cases, optical music recognition software may treat these instances as bowed tremolandi due to the knowledge of the complete semantics of the notation at the time of recognition. However, marking these as tuplets is the recommended practice.

In some situations, a tuplet is made up of events in different measures. As this raises the issue of non-concurrent hierarchies, it is not possible to encode such situations with the <tuplet> element described above. Therefore, MEI offers the <tupletSpan> element, which is member of the model.controlEventLike class. It is nested inside of <measure>, following all the measure’s <staff> children. It uses the same attributes as <tuplet> to describe tuplets, but instead of nesting all affected notes inside itself, it references the @xml:id values of all affected notes in its @plist attribute and the initial and terminal notes of the tuplet using @startid and @endid attributes. This configuration allows tuplets to cross beams or measure boundaries. The following example demonstrates a typical example of such hierarchy-crossing tuplets:

4.3.5Articulation and Performance Instructions in CMN

This section introduces elements and attributes which may hold CMN-specific performance instructions. The functionality described herein is related to the @artic attribute and <artic> element introduced in 2 Shared Concepts in MEI. The following elements are relevant in this context:

4.3.5.1Arpeggio and Glissando

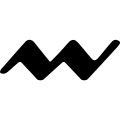

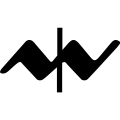

In CMN, the notes of a chord are sometimes performed successively rather than simultaneously. This behavior, called arpeggiation, is normally indicated using a vertical wavy line preceding the chord. MEI offers the <arpeg> element to describe arpeggios. This element is a member of the model.controlEventLike.cmn class and, like other members of this class, uses the @staff, @layer and @tstamp or the @startid and @plist attributes to connect it to the affected chord.

For arpeggios that involve chords spanning multiple staves as a continuous arpeggio (instead of two separate arpeggios), the @plist attribute should be used to point to all affected <chord> and single <note> elements’ @xml:id attributes. Therefore, the use of the @plist attribute is sufficient in many cases, so that other attributes from above may be omitted.

The usual direction for the performance of an arpeggio is from lowest note to highest, but this is not always the case. The customary signal of an downward arpeggio is an arrowhead added to the bottom of the wavy line. The indication of the presence of an arrowhead and the direction of the arpeggio are handled separately, however. The @arrow attribute indicates the presence of an arrowhead in the arpeggiation sign, while the @order attribute records the preferred sequence of notes. Béla Bartók uses a wavy line behind the chord to indicate a downward arpeggio. In such cases, the @ho attribute can be used to indicate the offset from the usual position.

The following examples illustrate various ways in which the arrow and order attributes may be employed. The default visual rendition and performance are assumed in the absence of both attributes, while the typical downward arpeggio is indicated by the presence of both attributes. The last two possibilities occur less frequently, but are sometimes appropriate: The presence of the arrow attribute without the order attribute may be used in those cases where the arrowhead is redundant but is added to the symbol for the sake of consistency or when the direction of successive arpeggios changes frequently. The last possibility, an order attribute without an arrow attribute, is ambiguous; however, it can be used as an encoding shortcut since a downward arpeggio must have a visual indication of its direction to distinguish it from the upward arpeggio; therefore, the presence of the arrowhead can be implied.

A third, and somewhat counter-intuitive, value for @order, nonarp, indicates that no arpeggio shall be performed. Normally rendered as a bracket instead of a wavy line, this form of arpeggio is used to indicate a non-arpeggiated chord intervening in a sequence of arpeggiated ones. This is common in music for the harp, where arpeggiation is the usual method of performing chords and deviation from the norm must be explicitly indicated.

Whereas an arpeggio ‘staggers’ the onset times of the notes of a chord, a glissando denotes a situation where the pitch ‘slides’ from one note to another. It makes no difference whether this slide produces distinct intermediate pitches (as on the piano) or not (as on the trombone), though the latter is sometimes referred to as portamento. The visual appearance of a glissando, which MEI encodes as <gliss>, is normally a line connecting two notes in the glissando.

The <gliss> element is a member of the model.controlEventLike class and therefore, like other control events, it occurs inside a measure after the staves and uses its @staff, @layer, @tstamp, @tstamp2, @startid and @endid attributes to connect it to the affected notes or chords. It is a semantic error not to specify a starting point attribute. The visual appearance of the indicating line may be recorded in the @lform and @lwidth attributes.

4.3.5.2Bend

A bend is a variation in pitch (often microtonal) upwards or downwards during the course of a note. Typically, the performer attacks the note at ‘true’ pitch, changes the intonation, then returns to true pitch. The <bend> element can also be used for so-called scoop, plop, falloff, and doit performance effects. It should not be used for laissez vibrer (l.v.) indications. As with other elements in the model.controlEventLike class, the starting point of the bend may be indicated by either a @tstamp, @tstamp.ges, @tstamp.real or @startid attribute. It is a semantic error not to specify a starting attribute.

4.3.5.3Tremolandi

CMN has two slightly different concepts which are both called tremolo. The first is a rapid repetition of a single pitch or chord, whereas the second is a rapid alternation between two different notes or chords. In addition, either species of tremolo may be measured or unmeasured. A measured tremolo is an abbreviation for written-out notation; that is, the tremolo is intended to be perceived as notes with distinct rhythmic values. On the other hand, in an unmeasured tremolo no specific number of alternations is intended.

For the repetition of a single note or chord, MEI offers the <bTrem> (bowed tremolo) element, which is a member of the model.eventLike.cmn class, meaning it is encoded following the normal course of musical events within a <layer>. It holds exactly one <note> or <chord> element that is to be repeated.

The @unitdur attribute value indicates the exact note values in an aural rendition of a measured tremolo, i.e., quarters, 8ths, and so on. The @stem.mod attribute must also be explicity set on the child <note> or <chord> element for a complete visual representation. The example above shows a short excerpt from the second movement of Franz Schubert’s String Quartet in G major, D. 887.

However, the number of slashes present on the note may disagree with the number of slashes that should be present according to the @unitdur attribute, especially in music manuscripts.

Note that within beams the number of slashes should be adjusted anyway.

The <bTrem> element can be used as shorthand for a tuplet consisting of repetitions of a single note or chord. This kind of markup may be the result of an optical music recognition process in which complete semantics cannot be determined a priori. When used this way, the @num attribute on <bTrem> can record a number to be rendered along with the pseudo-tuplet. In spite of this capability, the <tuplet> element is preferred. This makes the following examples’ visual appearance equal, but not necessarily their semantics.

In the case of alternating pitches, MEI offers the <fTrem> (fingered tremolo) element. While it mostly behaves the same as <bTrem>, a fingered tremolo requires exactly two child elements, either being a <note> or <chord>. The @unitdur attribute value indicates the exact note values in an aural rendition of a measured tremolo, i.e., 4ths, 8ths, 16ths, etc. The number of beams present in the source is captured by the @beams attribute.

Similar to <bTrem>, here the number of beams present may disagree with the rhythmic value indicated by the @unitdur attribute, especially in manuscript sources. The number of so-called ‘floating’ beams, which are not attached to stems, may be encoded in the @beams.float attribute.

4.3.5.4Fermata

A very common feature of music notation from the CMN period is the so-called ‘fermata’ (or ‘corona’ in Italian). It is usually written as a dot above or below an arc. It may stand above or below the staff it affects with its ‘open’ side usually facing towards the staff. A fermata indicates that a related note or rest should be held longer than its written duration would normally require. Sometimes, a fermata occurs over or under a bar line to indicate a pause or even the end of a phrase or section.

In MEI, fermatas may be encoded using an attribute on elements like <note>, <chord> or <rest>. This attribute allows placement of a fermata above or below the element to which it’s attached.

However, if there is further (visual) information about the fermata that should be

addressed in the encoding, MEI offers the <fermata> element. This element, which is a member of the model.controlEventLike.cmn class and therefore requires the use of such attributes as @staff, @layer, @tstamp and @startid, allows specification of the orientation of the fermata using its @form attribute. In addition, the @shape attribute may be used to indicate whether the fermata is rendered as the common semicircle

("curved"), a semisquare

("curved"), a semisquare  ("square"), or a triangle

("square"), or a triangle  ("angular"). If the fermata should be rendered using some other symbol, a user-defined

symbol may be referred to using an @altsym attribute or the @glyph.name and @glyph.num attributes respectively.

("angular"). If the fermata should be rendered using some other symbol, a user-defined

symbol may be referred to using an @altsym attribute or the @glyph.name and @glyph.num attributes respectively.

4.3.5.5Octave Shift

An indication that a passage should be performed one or more octaves above or below its written pitch is represented by the <octave> element.

Its @dis and @dis.place attributes record the amount and direction of displacement, respectively. The @lform attribute captures the appearance of the continuation line associated with the octave displacement. The starting point of the octave displacement may be indicated by either a @tstamp, @tstamp.ges, @tstamp.real or @startid attribute, while the ending point may be recorded by either a @tstamp2, @dur, @dur.ges or @endid attribute. It is a semantic error not to specify one starting-type attribute and one ending-type attribute.

4.3.6Instrument-specific Symbols in CMN

CMN contains a number of symbols which are closely related to a specific instrument. MEI offers elements for three of these symbols, namely breath marks, harp pedal diagrams, and piano pedals.

4.3.6.1Breath Marks

A breath mark indicates a point at which the performer of a wind instrument or singer may breathe. It is sometimes also used to indicate a short pause or break for instruments not requiring breath, which allows it to also serve as a guide to phrasing. In MEI, breath marks are encoded using the <breath> element, which is a member of model.controlEventLike.cmn. It is a semantic error not to specify a starting point attribute.

The usual sign for the breath mark is a comma; however, other visual forms of the breath mark may be indicated using the @altsym attribute (see chapter 2.4 User-defined Symbols for further details).

4.3.6.2Harp Pedals

Modern harps have seven pedals which allow adjustment of their strings to different pitches. The settings for these pedals occur at the beginning of the harp notation and/or whenever it is necessary to change the harp’s tuning. These settings may be rendered using letter pitches (in the order of the pedals from left to right) or in a diagrammatic fashion, such as the form invented by Carlos Salzedo.

In MEI, harp pedal settings are encoded using the <harpPedal> element. It is a member of the model.controlEventLike.cmn class and is therefore placed within <measure>, following all <staff> children. The @staff and @layer attributes may be used to assign it to a certain <staff> or <layer>. Either a @tstamp or @startid attribute must be used to indicate the placement within the measure (see 4.2.6 Timestamps and Durations and 13 Linking Data for further details about those linking mechanisms).

The musical intention of the element is described using the @c, @d, @e, @f, @g, @a and @b attributes, which affect the corresponding strings of the harp. All of these attributes may take the values f (flat), s (sharp) or n (natural), where a natural is the default value, which is assumed when one of these attributes is not specified.

In the first diagram of the preceding example, the B, and E pedals are in the flat position, while the C pedal is in sharp position. The other, non-specified pedals are in the natural position.

4.3.6.3Piano Pedal

Music for piano also often includes indications of the use of pedals. In MEI, these symbols are encoded using the <pedal> element. As a member of the model.controlEventLike.cmn class, it is located within <measure> and refers to a staff, layer and timestamp using the @staff, @layer and @tstamp attributes. Alternatively, the @startid attribute may be used to identify a <note> or <chord> to which the mark should be assigned.

The meaning of the mark is captured using the @dir attribute, which provides the following values:

down: depress the pedal

up: release the pedal

bounce: release, then immediately depress the pedal again

half: depress the pedal half way

To specify the pedal, that has to be used, the @func attribute allows the following values:

sustain:

The sustain pedal, also referred to as the "damper" pedal, allows the piano strings

to vibrate sympathetically with the struck strings. It is the right-most and the most

frequently used pedal on modern pianos. (Often marked with:  )

)

soft: The soft pedal, sometimes called the "una corda", "piano", or "half-blow" pedal, reduces the volume and modifies the timbre of the piano. On the modern piano, it is the left-most pedal.

sostenuto:

The sostenuto or tone-sustaining pedal allows notes already undamped to continue to

ring while other notes are damped normally; that is, on their release by the fingers.

This is usually the center pedal of the modern piano. (Often marked with:  )

)

silent: The silent or practice pedal mutes the volume of the piano so that one may practice quietly. It is sometimes a replacement for the sostenuto pedal, especially on an upright or vertical instrument.

4.3.6.4Fingering

A common feature for keyboard music is fingering, indicating the finger, which should be used to play a single note. Basic fingering can be encoded in MEI using the <fing> element, which is a member of the model.fingeringLike class, and thus part of the model.controlEventLike class.

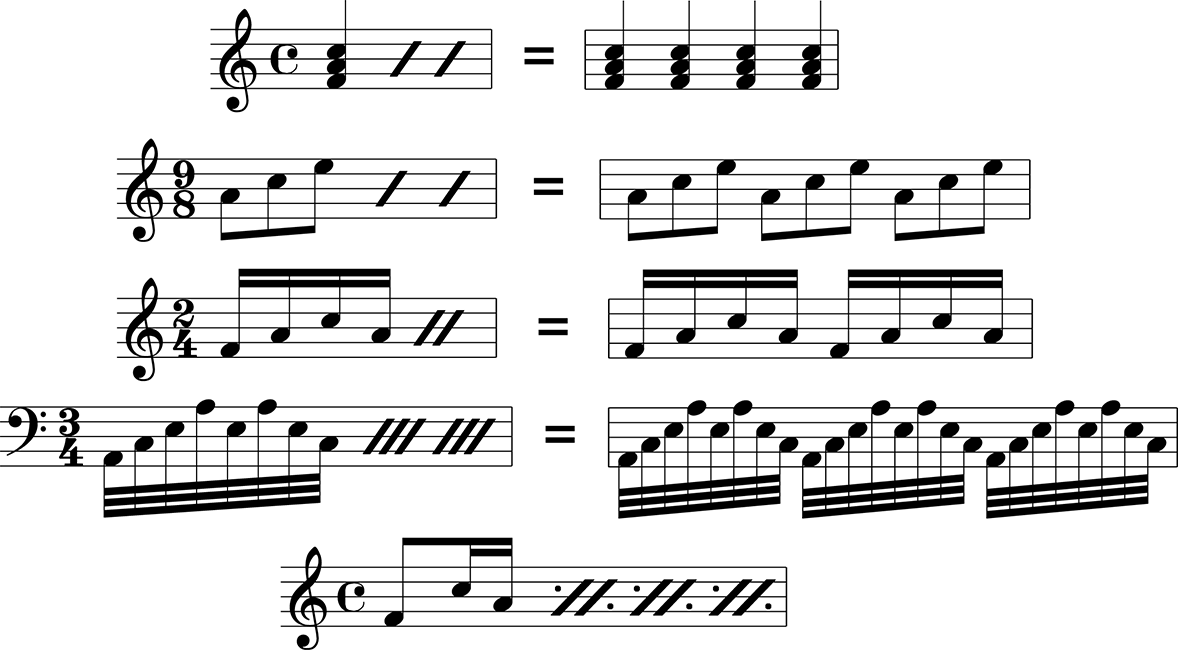

The following example, taken from Charles-Louis Hanon’s Le Pianiste virtuose, shows typical fingering:

4.3.7Ossia

The term ossia, Italian for "or", denotes an alternative for a certain passage which is provided by the composer without any preference one alternative over another. An ossia often provides a simpler (easier to perform) version of the original content. Another frequent use case for ossia is the provision of indications about performance practice, such as an alternative version with ornamentation written out in full. In all cases, it is up to the performer to choose between the alternatives.

Most often an ossia is rendered above the main staff on a reduced-size staff. Sometimes, however, the alternate material occurs on the same staff as the primary text, but in a separate layer. In this case, the alternative material is usually rendered in small-sized notation on the normal-sized staff. For both situations, MEI offers the <ossia> element, which may be nested either inside <measure> to reflect an ossia on a separate staff, or inside <staff> to reflect an inline ossia in a separate layer. The following example demonstrates an ossia on a separate staff:

The example above shows a <oStaff> element and a <staff> element within <ossia>. This mechanism allows one to distinguish between the "regular" and the "alternative" content: The "normal" staff goes in line with the preceding measure’s staff, the <oStaff> contains the alternative and is printed in reduced size above. In combination with the presence of an @n attribute multiple simultaneous ossia staves may be encoded.

All staves within <ossia>, even the alternative ones without a direct reference, obey the definitions of the associated <staffDef>, which can be derived from the value of the @n attribute. Alternatively, a separate <staffDef> may be given at the beginning of the contained <layer> element(s).

In case of an inline ossia, the alternative content is held in an <oLayer> element, as seen in the following example:

4.3.8Cue

Cue notes are smaller notes that usually occur in an orchestral or vocal part and are not to be played or sung by the corresponding musician, but by other instruments or singers. Cue notes are used for orientation, i.e., to follow the music during longer pauses and to find the correct re-entry point more easily. In MEI the @cue attribute is available to indicate such notes.

Most often cue notes occur in a group rather than one by one. This is because usually a whole layer of another part is inserted as a cue. Therefore, a complete <layer> can also be marked as cue.

If the voice from which the cue notes originate is also encoded, they should refer to their sounding counterpart with the @corresp attribute.

Cue notes must not be confused with other small notes such as grace notes or fiorituras.

4.3.9Directives and Rehearsal marks

In CMN scores, there is often a large number of natural language instructions. Some of them concern the loudness and the speed of the performance, in which case MEI offers the elements <dynam> (described at 4.3.3 Dynamics in CMN) and <tempo>. In other cases, however, they provide other instructions for the performer. Instead of providing separate elements for all possible types of such directions, MEI offers the generic <dir> element. Although this element is not CMN specific (it is defined in 2 Shared Concepts in MEI), it is frequently used in this repertoire.

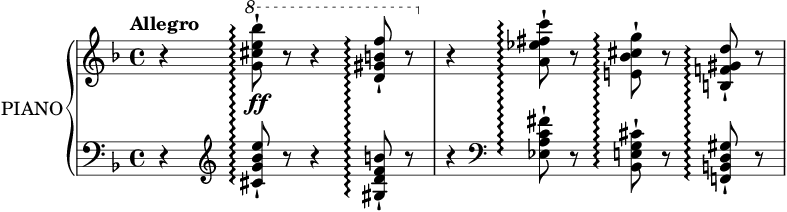

4.3.9.1Tempo changes and other directives

A tempo or character indication is often provided above the topmost staff of the first measure of a score, movement, or section. This indication, such as "Allegro moderato" or "Andante maestoso", may be regarded as a label. Though it is possible to label the movement, etc. using a @label attribute attached to the enclosing structural entity (that is, on <mdiv> or <section>), it is often required to capture the exact position, spelling, or other features of the label as found in the underlying source material. In these cases, an element is necessary.

Labels which address the tempo at which the music should be performed should be encoded using the <tempo> element, which is a specialized form of <dir>. <tempo> is a member of the model.controlEventLike class and as such occurs as a child of <measure>, following all <staff> children. Its @staff, @layer and @tstamp attributes are used to ensure correct semantic positioning, and @place indicates a visual position with respect to the staff.

4.3.9.2Rehearsal marks

Rehearsal marks are another specialized kind of directive. Consisting of letters, numbers, or a combination of both, rehearsal marks are used in scores and corresponding performer parts to identify convenient points to restart rehearsal after breaks or interruptions. For this reason, they are often visually emphasized by placing them within a square or circle. In MEI, they are encoded using the <reh> element, which holds the textual content of the rehearsal mark. It is a member of the model.controlEventLike.cmn class. The visual rendition of the rehearsal mark, including the surrounding shape, may be captured using the <rend> element described in chapter 9.2.2 Text Rendition.

The following detail from an edition of Hector Berlioz’ Symphonie Fantastique shows a typical example:

As rehearsal marks usually are placed at the beginning of a measure the @tstamp attribute may be omitted. To place it anywhere else the @startid, @tstamp or even @ho attributes could be used.

The following example demonstrates how rehearsal marks often apply to more than one staff. In this instance, the rehearsal mark is placed above staff 1 and below staves 7 and 11.

4.3.10Repetition in CMN

Repetition is a characteristic feature of music. Many musical forms rely on repetition (sometimes with modification) of distinct sections of the music. Repetition in this sense can be thought of as ‘structural’. At the same time, composers and engravers of music often use local symbols for repeating smaller portions of music instead of writing them in full more than once. In this case, the repetition is better defined as a species of abbreviation.

4.3.10.1Structural Repetition

Large-scale structural repetition, utilizing <section> and <expansion> elements, is discussed in section 2.1.2.2 Content of Musical Divisions. This section will focus on repetition within sections.

4.3.10.2Measure-Level Repetition Symbols

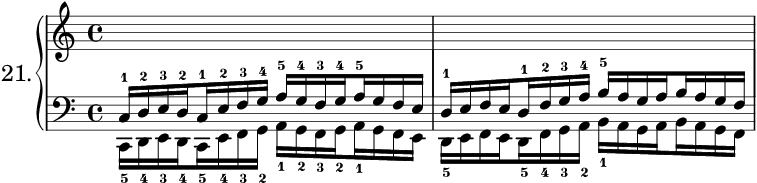

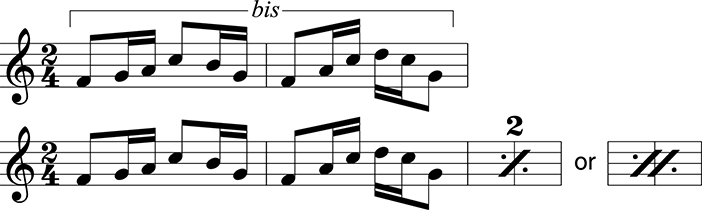

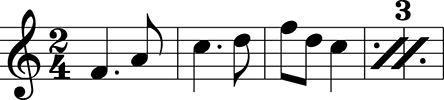

In addition to repetition at the section level, CMN includes a number of different symbols for measure-level repetitions. Many of these symbols are found in manuscripts and may be regarded as personal conventions of their respective authors. Some signs, however, have been widely adopted. For example, it is common to indicate the repetition of a single beat or an entire measure with one or more diagonal lines, sometimes with dots at the upper left and lower right, much like a percent sign. The illustration below contains the most common signs:

In general, MEI places primary emphasis on the capture of the semantic meaning of symbols, not their visual rendition. In this case, the focus is on the material being repeated, for example, a beat, a measure, a 2-measure fragment, etc. The following elements are provided for this purpose:

The <beatRpt> element is used to represent a single repeated beat. Its visual rendition can be recorded using the @slash attribute. This attribute indicates the number of slashes required to render the appropriate repeat symbol, which, as demonstrated in the preceding figure, depends on the rhythmic content of the beat being repeated. When a beat that consists of a single note or chord is repeated, the repetition sign is typically rendered as a single thick, slanting slash; therefore, the value 1 should be used. The following values should be used when the beat is divided into even notes: 4ths or 8ths=1, 16ths=2, 32nds=3, 64ths=4, 128ths=5. When the beat is comprised of mixed duration values, the symbol is always rendered as 2 slashes and 2 dots.

In addition to its indication of a repeated beat, the beatRpt element is sometimes used in popular music notation, especially in guitar or percussion parts, to indicate a repeated rhythmic pattern. The <beatRpt> element can be used, but when these parts require durations longer or shorter than a beat, note elements with appropriately-shaped note heads should be employed instead.

The <mRpt> element is available for repetition of an entire measure. Like <mRest>, it must be the sole child of <layer>, no other events should be used. The @n attribute of <mRpt> should not be used to record the number displayed above the measure in the figure below. Instead, the numbering of repetitions of the written-out measure can be enabled using the @multi.number attribute available on the <scoreDef> and <staffDef> elements.

The <halfmRpt> element represents the incorrect, but frequently found, use of the measure repeat (or similar) sign to indicate repetition of half of a measure. This practice mostly occurs in hand-written notation and usually involves the repetition of the second half of a measure in duple time. This element is necessary because the function of the symbol, not the visual symbol itself, is of primary importance. The following example from the beginning of Beethoven’s Waldstein sonata illustrates such usage:

As seen in the example above, it is possible to continuously repeat half measures, even across bar lines.

The <mRpt2> and <multiRpt> elements (like the <multiRest> element) never occur in scores, only in performer parts, where it is often necessary to abbreviate the notation due to page size limitations.

The <mRpt2> element represents repetition of a 2-measure fragment, while <multiRpt> is for repetition of fragments longer than two measures. In modern publishing practice, repeats of more than two measures are written out using repeat signs. This element is provided, however, for handling non-standard practices often found in manuscripts. The @num attribute on <multiRpt> records the number of preceding measures to be repeated.

All elements described above allow for association of the sign with a symbol in a digital facsimile (via the @facs attribute) and with a user-defined symbol (using @altsym). See 12.1 Facsimiles and 2.4 User-defined Symbols for further details. In addition, the @expand attribute is available on the foregoing elements to inform a rendering process whether to use the repeat symbol or the full content represented by it. A value of true indicates that the content should be displayed, while a false value means to show only the repeat symbol.

4.4Common Music Notation Ornaments

This module includes elements and attributes for the encoding of ornaments typical of ‘Common Music Notation’ (CMN). Ornaments are formulae of embellishment that can be realized by adding supplementary notes to one or more notes of the melody. In written form, these are usually expressed as symbols written above or below a note, though some have a more complex written expression, such as those that involve multiple notes and/or include grace notes.

These symbols may have different resolutions depending on a large number of factors, such as historical context, national boundaries, composer, scribe, etc. The elements described here, therefore, are not bound to a specific symbol; they are, instead, meant to encode the encoder’s interpretation of a symbol and its position on the staff.

Nonetheless, in order to establish common ground, the guidelines suggest commonly accepted symbols and realizations for the ornaments supported by MEI.

The following sections will introduce each element in detail for all types of ornaments supported.

4.4.1Encoding Common To All Ornaments

When encoding CMN, ornaments should be encoded within a <measure>, following the <staff> elements, and connected to events on the staff via attributes. The @startid attribute is used to refer to the @xml:id of the starting note. Additionally, if the ornament involves more than one events on the staff, the @endid attribute can be used to anchor the ornament to a concluding event.

The following example demonstrates the encoding of a mordent over a middle C:

Alternatively, the relationship of an ornament to a note can be expressed in terms of beats with the attribute @tstamp. If the ornament involves more than one event on the staff, the @tstamp2 attribute can be used to indicate the ending time stamp, as is explained in section 4.2.6 Timestamps and Durations. These methods may also be utilized simultaneously.

The following example shows the use of @tstamp for an ornament. Assuming that the following measure is in 2/2, the ornament (in this case, a mordent) is related to the note on the second beat.

The relationship between an ornament and the notes on staff must always be encoded. It is, in fact, a semantic error not to specify a starting event or time stamp for an ornament.

In their resolution, ornaments will involve auxiliary notes, which typically follow the key signature or the scale of the current key. When the ornament involves other chromatic auxiliaries, an accidental is expressed next to or above the ornament sign. The attributes @accidlower and @accidupper, available on all ornaments described in this chapter, can be used to record this accidental. The attribute values ‘upper’ and ‘lower’ indicate whether the accidental is associated with an upper or lower auxiliary note, not the position of the accidental sign.

4.4.1.1Overriding Default Resolutions

The symbols and sounded resolutions suggested for each ornament in this chapter are to be considered defaults. Nevertheless, because of the great historical and geographical variance in the notation of ornaments, the encoder is given methods to override the default resolutions.

It is possible, for example, to specify in the <meiHead> a new default sounded resolution for an ornament. As discussed in the section 3.4.2 Encoding Description, the element <encodingDesc> holds a description (optional, but recommended) of the methods and editorial principles which govern the transcription or encoding of the source material. Let us take a trill as an example. The section regarding 4.4.3 Trills does not set a specific number of alternations between the principal and secondary notes; the encoder, however, may specify an exact number in the encoding description.

Alternatively, resolutions can be defined on a case-by-case basis by encoding a specific resolution using the <choice> element. See the section 4.4.3.1 Special Cases below for an example of a specific resolution of a trill.

4.4.2Mordents

A mordent is an ornament that involves an auxiliary note a step above or below the principal note. The presence of a mordent is encoded with the <mordent> element and its attributes:

It is recommended, but not required, to use the attribute @form to encode the typology of mordents. Two common types are supported: those mordents that involve a note lower than the principal note, and those that involve a note higher than the principal note.

The attribute @form accepts the following values:

upper:

usually corresponding to the symbol:  . This mordent is commonly performed as the principal note, followed by its upper

neighbor, with a return to the principal note.

. This mordent is commonly performed as the principal note, followed by its upper

neighbor, with a return to the principal note.

lower:

usually corresponding to the symbol:  . This mordent is commonly performed as the principal note, followed by its lower

neighbor, with a return to the principal note.

. This mordent is commonly performed as the principal note, followed by its lower

neighbor, with a return to the principal note.

The following example demonstrates the encoding of simple mordents:

Occasionally, mordents can be longer, employing five notes instead of three. The @long attribute can be used to identify mordents of this type. The following example shows the encoding of a long mordent:

4.4.3Trills

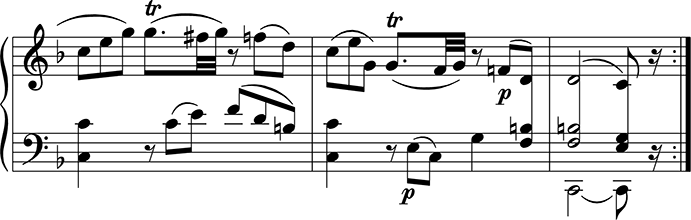

Trills are a type of ornament that consists of a rapid alternation of a note with one a semitone or tone above. A trill is encoded with the <trill> element and its attributes:

Trills in modern notation are usually expressed with the abbreviation "tr" above a note on the staff. Often the abbreviation is followed by a wavy line that indicates the length of the trill.

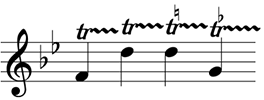

The following example demonstrates the encoding of simple trills:

It has been specified earlier that it is a semantic error not to encode a starting event or time stamp for an ornament. This starting point of a trill can be expressed with the @startid attribute and/or with the @tstamp attribute. Specifying the end point is not required, although the @tstamp2 or @endid attribute may be used to imply the use of a wavy line extender as shown in this example:

When giving an end point to trills, the @extender attribute should also be added, to indicate the presence or absence of a line extender. Notice, that the note referenced in @endid is not part of the trill itself, just like in glissandos.

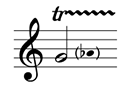

Chromatic alterations of auxiliary notes are occasionally expressed on the staff using small notes enclosed in parentheses, as shown in the example below. However, the attribute @accidupper is still to be used to encode the alteration. Display of the auxiliary note in this ‘cautionary’ manner is left to down-stream rendering processes.

Some trills may be introduced by a turn or followed by an inverted turn leading to the next note (see Le garzantine, Musica 2003, p. 911). In such cases, the trill is encoded as in previous examples and associated with the principal note. Starting or concluding turns are notated on the staff (in <layer>) as 4.2.5.1.2 Grace Notes.

The following example, from a keyboard sonata by Joseph Haydn, shows a trill with concluding grace notes (called Nachschlag):

4.4.3.1Special Cases

Symbols and abbreviations for trills have changed and evolved considerably throughout history. Strategies to clarify the encoding and interpretation of ornaments have been discussed in section 4.4.1.1 Overriding Default Resolutions above. However, in order to aid the encoder in making educated choices in the encoding of non-standard trills, this section shows two examples diverging from modern standard use.

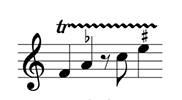

The abbreviation "tr" followed by a wavy line spanning multiple notes is sometimes used to indicate multiple trills:

The encoding of this kind of trill may vary depending on the purpose of the encoding. For representation of the source, a single trill is sufficient:

To support analytical and aural rendering applications, however, each trill may be explicitly encoded, as the following example demonstrates:

However, when it is necessary to support multiple outputs, use of the <choice> element and appropriate sub-elements is recommended. In this case, the <orig> and <reg> elements can be used to represent the original source and a regularization provided by the editor, respectively:

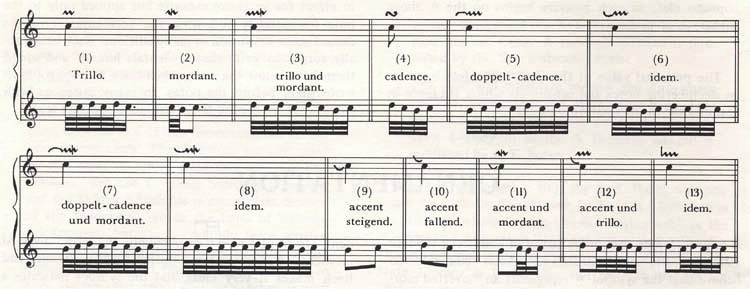

Another situation that requires disambiguation of an ornament’s name and its potential rendition is due to the fact that the symbols for trills and mordents have been often used interchangeably in the past. The following example, taken from Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (1720), shows a trill (Trillo) identified by the symbol associated with a mordent in modern practice. Nonetheless, J.S. Bach’s suggested resolution should be encoded with a variant of the procedure presented above.

In the example below, the child elements of <choice>; that is, <orig> and <reg>, represent non-exclusive options; that is, both may be processed by applications that aim to support both visual and aural renditions.

Depending on the purpose of the encoding, it may be more convenient to encode the regularized text within the stream of events, along with a corresponding choice with regard to the existence of the trill marking, as in the following example:

The <orig> element contains the single-note-with-trill transcription of the original text, while the <reg> element represents the realization-without-trill version.

This approach facilitates substitution of the realization of the trill for the original written note (as well as the opposite procedure) and is therefore the recommended markup for applications where exchange of this kind is desirable.

4.4.4Turns

A turn is an ornament that typically consists of four notes: the upper neighbor of the principal note, the principal note, the lower neighbor, and the principal note again.

The presence of a turn is encoded with the <turn> element and its attributes:

It is recommended, but not required, to use the attribute @form to encode the typology of the turn.

The attribute @form accepts the following values:

upper:

usually corresponding to the symbol:  . This turn is commonly performed beginning on a note higher than the principal note.

. This turn is commonly performed beginning on a note higher than the principal note.

lower:

usually corresponding to the symbol:  . This turn is commonly performed beginning on a note lower than the principal note.

. This turn is commonly performed beginning on a note lower than the principal note.

The following example shows the encoding of a simple turn:

Turns can sometimes be performed after the principal note (usually on the second half of the beat, see Read 1979, p. 246) and leading to the following event. To indicate this, the turn symbol is typically written in between the principal note and the next. These kind of turns are encoded with the attribute @delayed.

The following example from Beethoven’s piano sonata no. 1 in F minor, op. 2, no. 1, mvmt. 2 demonstrates the encoding of turns with the @delayed attribute. Note that the @tstamp attribute indicates the actual starting point in time, while @startid points to the principal note.

4.4.5Other Ornaments

CMN ornaments that are not mordents, trills, or turns can be encoded with a generic <ornam>.

This element allows the encoder to represent ornaments as textual strings (e.g., with a Unicode symbol) or with a user defined symbol. Chromatic auxiliaries can be represented with @accidlower and @accidupper. The <ornam> element can also be a control element. That is, it can be linked via its attributes to other events. The starting point of the directive may be indicated by either a tstamp, tstamp.ges, tstamp.real or startid attribute, while the ending point may be recorded by either a tstamp2, dur, dur.ges or endid attribute. It is a semantic error not to specify a starting point attribute.